At the center of that, however, are the warfighters and decision makers who are most reliant on critical, accurate and timely data to carry out the department's mission, said the department's Chief Data Officer.

"This strategy is for warfighters and decision makers," said David Spirk, who spoke at the National Defense Industrial Association. "It's 100 percent focused on improving the speed and execution of decisions — to support informed decision making, to improve situational awareness and knowledge at every level, to improve our ability to anticipate events and resource needs before they were known."

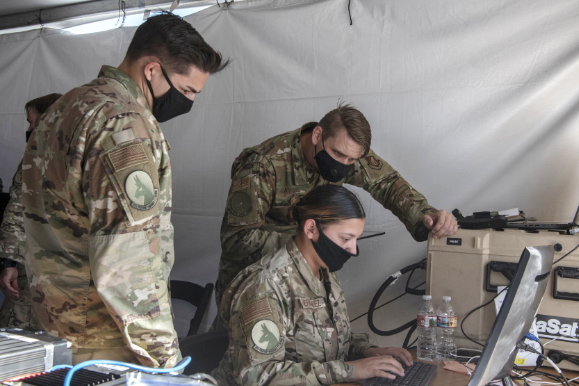

U.S. Air Force airmen monitor battlespace movements at a

simulated austere base during the Advanced Battle Management

System exercise at Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., Sept. 3, 2020.

Photo is by Air Force Tech. Sgt. Cory D. Payne.

To ensure the fastest, smoothest distribution of data to warfighters, decision makers, and even artificial intelligence systems, the DoD data strategy lays out a plan to, among other things, standardize how data is collected, categorized, tagged and distributed.

The strategy sets goals for the department to build a data environment that makes it easy for would-be users of data to not only find what data they need, but to also get access to it — wherever that is. That data must also be adequately described in language that is standardized across the department, so that would-be users can easily identify its relevance to their portion of the mission.

Also important within the strategy is that data be trustworthy. The strategy calls for development of standards to ensure that when users get ahold of data, for instance, it's always accompanied by additional, standardized information that makes it clear where that data came from.

The strategy demands a lot of changes from those across the department who collect, generate and maintain data, so that users in other areas can always have what they need, when they need it. Spirk said getting those people on board will be critical to the success of the data strategy.

One way to do that, he said, is creation of chief data officer positions, where appropriate, to ensure the data strategy is being implemented and, also, to build relationships and trust between agencies so that data can move to where it needs to be more efficiently than it may be doing now.

Spirk said the department will know it has been successful in implementing its data strategy by the responses of the warfighters.

"The measure of our success is going to be a recognizably faster warfighting operation tempo," he said. "This will be achieved by treating data as a weapon system, effective partnerships and a collective focus. And when I say weapon system, I mean we need to think of the data ecosystem as the weapon system that fires the data and ensures it's available to our warfighters at the time and place they need it before they realize that they did.

The Defense Department is, perhaps, the biggest user of spectrum in the United States, said Frederick D. Moorefield, the Deputy CIO for Command, Control and Communications.

"DOD uses spectrum for almost everything wireless, everything from tactical radios that the soldier uses in the field, or in operations, to satellite communications, to radar that we use to track objects and devices," he said. "We use it for everything wireless."

The department's evolution in the EMS is necessary for the U.S. military's ability to effectively sense, command, control, communicate, test, train, protect and project force." Ellen Lord, undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment

For a long time, Moorefield said, DOD was uncontested in its use of the spectrum. That means either stateside or abroad, wherever the U.S. military went, it was able to use whatever portion of the spectrum it wanted to facilitate its own communications. Other nations weren't technologically capable of using spectrum. But that is no longer the case.

Now, due to the low-cost of entry into spectrum use and ubiquity of wireless communications equipment, any adversary, not just peer and near-peer competitors, has as much access to the spectrum as the Defense Department. That means that in any conflict, any adversary may be using spectrum crucial to the department and preventing the military from being able to use it. Adversaries may also use jamming techniques to actively block DOD from using portions of the spectrum.

"Technologies evolved and our peer competitors have improved and watched us over the years and have gotten smart," Moorefield said. "We're getting jammed on everything from GPS to our [unmanned aircraft systems.] That's why we have our counter-UAS program out there. Everything's getting interfered with. That is a contested environment. Everything's getting jammed."

It's not just on the battlefield where the U.S. can be jammed either, Moorefield said. Jamming is happening while doing training overseas and in other places as well.

"Just during our training and exercises, we're getting jammed," he said. "Stuff is going on — GPS is getting denied and jammed all the time in different countries. Our UASs are getting jammed and spoofed."

Navy Petty Officer 3rd Class Daniel Torotorres, a Puerto Rico

native assigned to the guided missile destroyer USS Ralph

Johnson, conducts maintenance on a data router in the Persian

Gulf, Oct. 1, 2020.

Photo By: Navy Petty Officer 3rd Class Anthony Collier

A soldier monitors air and ground position information on the

Windows and android tactical assault kits to get a common

operating picture that enhances situational awareness and

data sharing at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz., Sept. 16, 2020.

Photo is byJustine Ruggio, U.S. Army

Even stateside, Moorefield said, the department finds itself in competition in the electromagnetic spectrum with industries and communities around military bases.

"It is getting more and more crowded," he said. "At some of our bases we used to be able to go out and do training and testing and exercises — just go out and do whatever we wanted to do. But now, the surrounding neighborhoods and the surrounding communities are just getting more and more crowded using wireless. So that access that we used to use, and freedom that we used to have using the spectrum on those bases is diminishing as the communities are growing."

The department's electromagnetic spectrum superiority strategy is driven by three "C's," Moorefield said: a contested environment, spectrum congestion and spectrum constraint.

A contested environment, he said, means adversaries have gotten smarter in how they jam the spectrum. Even if an adversary isn't using a portion of the spectrum, he said, they can prevent the U.S. from using it through jamming.

"We have to figure out how to be smarter than them and develop capabilities to allow us to be able to get access to the spectrum whenever we need it, and however we need it and to also be able to deny the enemy the same access," Moorefield said. "We call that 'freedom of maneuver' within the electromagnetic spectrum."

The congested environment, he said, means there's simply more people wanting to use spectrum. That might mean stateside or abroad, in actual warfare or in training, the department will find that there's just a lot more users now of the electromagnetic spectrum than there have been.

"The spectrum space is getting more and more crowded," Moorefield said. "That includes 5G, the next G coming, SATCOM, tactical radios, commercial and federal — everybody's using spectrum more and more. So, we have a congestion problem, everything is crowded."

An illustration with an M1 Abrams tank firing. Graphic illustration

by Regina Ali, DOD

Finally, he said, there is constraint. Whereas the department in the past had more freedom to move about the spectrum when it needed to, domestic and international regulations have decreased the amount of spectrum available for military access.

"We don't have that big access and use that we used to have. DoD used to use a spectrum any way they wanted to. Those days are over," he said. "That constraint is limiting us in our ability to train as we fight."

To ensure that in the future the U.S. military has the ability to operate in the electromagnetic spectrum, the department has developed the "2020 Department of Defense Electromagnetic Spectrum Superiority Strategy."

"Superiority means being able to access the spectrum, use any frequency you want to, be able to maneuver ... and deny the enemy access to the spectrum at the same time," said Moorefield.

The strategy includes five goals to help the department attain that superiority:

1 Develop superior EMS capabilities.

2 Evolve to an agile, fully integrated EMS architecture.

3 Pursue total force EMS readiness.

4 Secure enduring partnerships for EMS advantage.

5 Establish effective EMS governance.

For the U.S. military to attain that superiority, there will need to be modernization and reform, new policies put in place, and new gear — all of that is spelled out in the strategy.

"The department's evolution in the EMS is necessary for the U.S. military's ability to effectively sense, command, control, communicate, test, train, protect and project force," said Ellen Lord, the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment."Modernizing to maintain competitive advantage over near-peer adversaries will enable DOD to assert EMS superiority and mitigate risks to U.S. national and economic security." One part of reform, said Moorefield, is a change in the way spectrum is managed today.

"Today, spectrum is managed by static frequency assignments and licenses. We have to get dynamic, flexible and cognitive to be dynamic enough to be able to move around at different frequency bands."

Also involved, and part of the strategy, is development of spectrum sharing capability. That means acknowledging that there are other users of a segment of spectrum the DoD wants access to, that there are benefits to U.S. commerce if the private sector or even other federal agencies have access to that spectrum, and then developing a system whereby more than one entity can take turns using that part of the spectrum when needed. That's not happened in the past, but it's happening now, Moorefield said.

Implementing the EMS Superiority Strategy enables us to take that bold action so we are able to dominate the spectrum in all domains and, if challenged, win against our enemies." Air Force Gen. John E. Hyten, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

EMS superiority will also involve new kinds of technology that are able to determine on their own what frequency they ought to be on at any time, Moorefield said. That technology will be able to assess the environment to see what else is using spectrum, and what part of it, and then find the best available portion of the spectrum to use to accomplish the communications it needs to accomplish -- all without the assistance of users.

"We're trying to get to autonomous kinds of operations, meaning machine-to-machine," he said. "You've got the machines talking to each other. You won't have to have segregated allocations. You'll have the machine built to be able to tune across a variety of different frequency bands. It'll listen within the environment. And it'll be talking to another machine and say I'm using this frequency; you move to another frequency."

Policy changes are needed, as well. The department's acquisition elements must be allowed to obtain the right kind of equipment to attain spectrum superiority, he said.

"We have to be able to reform acquisition [policies] so that they know that they can build capability to do that — to be able to be dynamic," he said. "Today we can't do that. The regulations don't support it. We have to reform the regulations to allow dynamic spectrum operations. We have to inform acquisition so they can now acquire those kinds of capabilities. We need to inform research and engineering so they can do the research and development, so that acquisition can purchase it."

There's a lot of equipment in the department's inventory today that was designed to operate in the EMS. But that equipment was built to operate in clearly-defined areas of the spectrum. Eventually, all that gear will need to be replaced with new gear that can operate more freely in the spectrum, and share spectrum with other pieces of gear. That's going to take several years to make the transition, Moorefield said. But along the way, new gear will be cognizant of the older equipment on the battlefield, and will be able to work alongside it.

"We've got old stuff out there, we've got medium stuff and we've got new stuff," he said. "As you do your tech refresh, and you implement the policies into the acquisition reform, to be able to build dynamic spectrum stuff, that new capability will be able to cohabitate around the old stuff because it now has that dynamic flexible operation. So it's not sitting on a single frequency. I don't care what your old stuff is doing, I'm going to operate around you. And when that old thing expires, then they're going to tech refresh and become dynamic. Over time, we'll get there. But it's going to take us time to do that."

Another big part of the superiority strategy is the blending of the electromagnetic warfare and electromagnetic spectrum management communities into one "electromagnetic spectrum operations" or EMSO community, Moorefield said.

"In the past, the electronic warfare community kind of did their own thing," he said. "They're out there doing jamming, electronic attack and the protect mission without any regard to the other communication equipment in the battlefield."

The result of that, he said, sometimes created spectrum "fratricide" on the battlefield, where blue force use of the spectrum to damage enemy forces also hurt other blue force operators.

"The guys on the ground were getting blasted — they couldn't even talk on their radios anymore because you got a big platform flying through and he's just blasting out, jamming the entire battlefield," Moorefield said.

The merging of the existing electronic warfare and EMSM communities into an EMSO community, he said, can fix this.

"This now blends this all together and forces us as a department to be able to orchestrate this battlefield," he said. "Now you have EW, you got all your other comms — whether it's tactical radios, radars, EW, all being orchestrated in the environment. Our goal is to develop a common operating spectrum picture so that the commander can see what those operations look like and he can command and control those operations, based on that spectrum picture."

The strategy doesn't lay out a timeline for how the Defense Department will get mastery of the EMS. Instead, Moorefield said, the strategy sets a "broad vision of where we go and how we get there."

What's clearer, he said, is the consequences of not achieving spectrum superiority.

"If we don't figure out how to dominate the spectrum space we're going to be at the mercy of our peer competitors," he said.

Air Force Gen. John E. Hyten, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said the 2020 Department of Defense Electromagnetic Spectrum Superiority Strategy is what the Defense Department needs to ensure U.S. warfighters continue to have freedom of action wherever they are asked to fight.

"The department is dedicated to a unified, holistic electromagnetic spectrum operations approach which ensures our freedom of action in the EMS at the time and place of our choosing," Hyten said. "We cannot expect military success in any domain if we fail to take bold action to ensure that the United States and its allies have freedom to act in the spectrum. Implementing the EMS Superiority Strategy enables us to take that bold action so we are able to dominate the spectrum in all domains and, if challenged, win against our enemies."

DoD feature articles authored by C. Todd Lopez, DoD New

New Spectrum Strategy Reveals DoD Plan to Master the Airwaves

Short of face-to-face conversation, wired internet or telephone land lines — a mystery to many young Americans — nearly every form of communication the Defense Department uses today, especially on the battlefield, is wireless. Some U.S. adversaries are working very hard to cut off that form of communication.

An illustration showing two MH60S Seahawk helicopters conducting a vertical replenishmentatsea with the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz. Graphic illustration by Regina Ali, DOD

The Defense Department released the "2020 Department of Defense Electromagnetic Spectrum Superiority Strategy." This document lays out how the military will guarantee its continued and unfettered access to the airwaves, or spectrum, which facilitates GPS, radio, satellite and cell phone communications. This document also reveals how the military plans to master that spectrum while on the battlefield.

"The rise of mobile systems and digital technology across the globe has placed enormous strain on the available spectrum for DOD's command, control and communication needs," said Dana Deasy, the department's CIO. "This strategy will help set the conditions needed to ensure our warfighters have freedom of action within the electromagnetic spectrum to successfully conduct operations and training in congested, contested and constrained multi-domain environments across the globe."

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of radiation frequencies that are used to transmit information wirelessly. While frequencies above 300 GHz make up infrared light, visible light, ultraviolet light, and x-rays, frequencies at 300 GHz and below are used to transmit information for cell phones, television, radio, satellite communications, GPS, hand-held two-way radios and even key fobs that lock and unlock cars.

Those who want to transmit information over those communication frequencies typically apply to the federal government for a license. This ensures that only one entity is attempting to use a frequency at a time.

There are hundreds of locations on the electromagnetic spectrum blocked out by the U.S. federal government — and by governments globally — for specific applications by specific users in every part of the world.