New IA-PRE program set to improve vetting process for COMSATCOM

To keep up with the growing demand for commercial satellite services and also ensure these services are secure from adversaries, the U.S. Space Force (USSF) is introducing a new program, IA-Pre, that will strengthen its cybersecurity posture and also make it easier for commercial industry to do business with the military.

USSF’s Commercial Satellite Communications Office (CSCO) has been in business for more than 25 years, said CSCO Chief, Clare Grason. Previously, the office was under the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) and is now in the process of transferring to the USSF. The office has about 100 people, including civilian, military and contractors and is charged with acquiring all commercial SATCOM services for the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD).

Clare Grason

CSCO is organized into two business units: the Enhanced Mobile Satellite Services program, which includes services provided by Iridium Satellite LLC, and the commercial SATCOM solutions program office, Grason said.

“We’re in essence a broker for both programs; regarding the EMSS program, we have the world’s largest family voice and data plan,” Grason likened. “It’s unlimited voice and data on the Iridium system for an unlimited number of users or devices. We’re operating as a mini telecommunications company, but sealed with DoD security procedures — we aggregate all the costs of doing business and we recover those costs by levying a rate upon our customers.”

“CSCO has the sole authority for the procurement of commercial satellite communications for the DoD, but also supports other federal agencies, some allied foreign military clients and NATO. The contracts vary in length and complexity,” Grason said. “Currently, there are more than 200 active contracts amounting to an estimated $5.2 billion lifecycle portfolio, or approximately $800 million of commercial SATCOM services per year.”

CSCO is a reflection of how the military has transitioned from purpose-built systems — designed specifically for, and built by, the military — to incorporating more commercial industry partnerships. Such partnerships help provide the military with the latest and most innovative technology and resiliency; at the same time, government contracts can give emerging companies a solid foundation as they continue to grow, strengthening the industrial base for critical technologies and helping to support competition in markets that might otherwise stagnate due to high cost-of-entry barriers.

“The more systems and capabilities we can leverage, the more resilient our architecture becomes, and it becomes more difficult for our pacing challengers to disrupt or dismantle our ability to complete missions,” Grason said. “We’ve also seen a steady increase in demand for commercial SATCOM through the rapid innovation that the industry is laying out,” Grason said. “They can be less ham-strung by bureaucracy that some MILSATCOM or purpose-built programs are tied to, and they’re able to get capabilities rolled out faster, and the technologies are acceptable to our user community for a wide range of use cases.”

“Private industry is investing in enhanced security mechanisms in a way they haven’t been in the past,” Grason added. “In many cases, there needs to be only modest investments from the government in order to obtain the security conditions we need. They’re able to get it to market quickly, and adapt solutions in an efficient manner.”

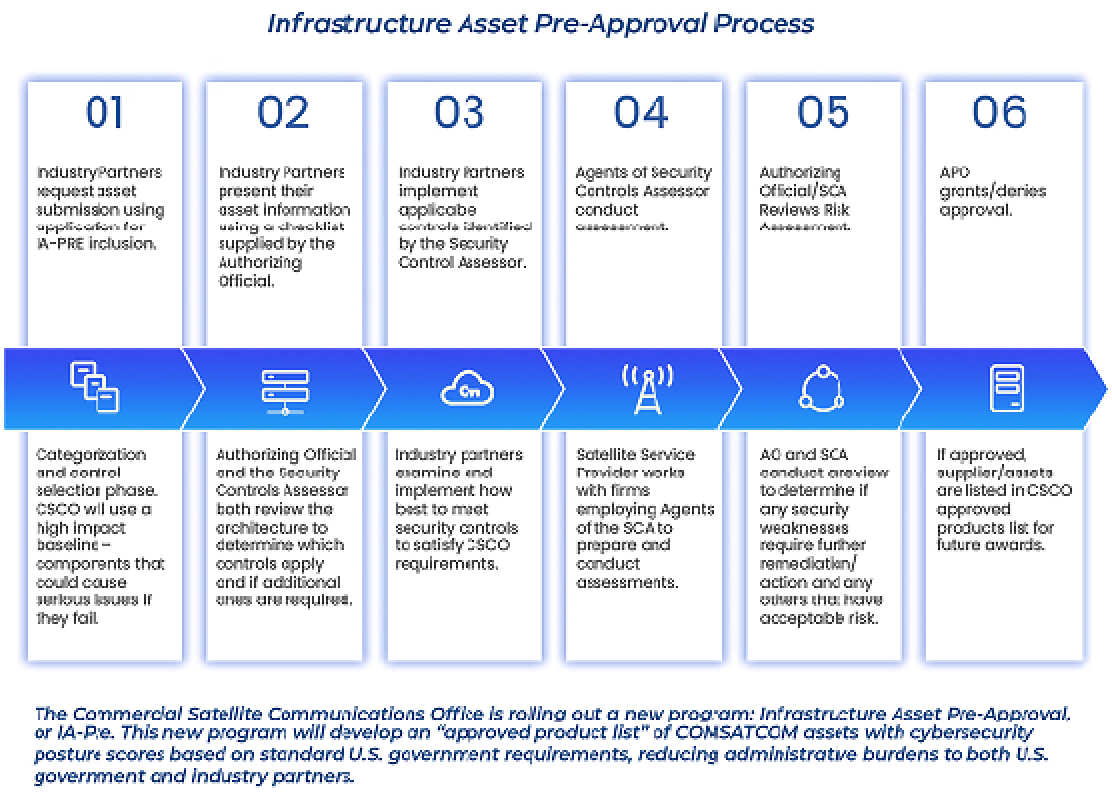

In a similar fashion, USSF is working to make it easier for these companies to work with the military. The Infrastructure Asset Pre-Approval Program is a new program within CSCO being rolled out this year, with the goal of developing an “approved product list” of COMSATCOM assets with cybersecurity posture scores based on standard U.S. government requirements and to enhance commercial asset security posture, reducing administrative burdens to both U.S. government and industry partners.

Jared B. Reece

“SATCOM is its own entity — it’s critical infrastructure,” said Jared B. Reece, manager of the IA-Pre program within CSCO. “People don’t think about how much of their data or what they do on a regular basis relies on satellite services – every component of the defense industrial base relies on SATCOM as a capability to the reliance of tractors and large agricultural companies on GPS and satellites.”

IA-Pre will replace a self-assessment process in which contractors submitted their requested system information to CSCO through a questionnaire for evaluation during the acquisition process. One drawback to this system was that contractors often found themselves submitting the same information, over and over again, every time they bid on a contract.

Under IA-Pre, industry partners will work with a third-party assessor to complete an assessment of their submitted assets against the established cybersecurity baseline for that asset, Reece said.

“Industry partners will have to prove that they do, in fact, meet the intent of baseline controls for this program, and that evaluation is sent to us to review, in submission with their asset,” Reece said.

“This will greatly enhance the cybersecurity of these systems,” Reece said. “We established a new baseline for commercial SATCOM because the need and use cases for COMSATCOM have changed dramatically over the last decade. Establishing a new baseline was critical in getting a greater understanding of the mission.”

“It really gives industry an idea of what we want from a cybersecurity perspective, what to shoot for within their company if they want to compete for government contracts,” Reece said. “So often, DoD tries to marry DoD policy to commercial systems, but what this [IA-Pre] does is basically create a policy designed for commercial systems in use by the DoD.”

Previously, cybersecurity was rated on a pass/fail basis. With IA-Pre, if an asset is not in compliance, the contractor can submit a Plan of Actions & Milestones (POAMs) that will allow them to use other methods to become compliant or provide mitigations to achieve an acceptable level of residual risk.

The program emphasizes on-site assessments for verification of cybersecurity compliance using third-party assessors certified and licensed by the U.S. Space Force Security Controls Assessor, Reece said.

The U.S. Space Force Authorizing Official (AO) will review the company’s cybersecurity assessment results for approval, Reece said. CSCO then will place the industry partner and the assessed assets into an approved platform list. That way, the company will no longer require a cybersecurity evaluation prior to the award of a contract for covered assets.

IA-Pre also contains provisions that may make it easier for small businesses to compete for these contracts, Reece said. Under the old system, a larger, “prime” contractor would have to consolidate security information that would then be submitted as part of their proposal. This could potentially expose small businesses to proprietary methods used by other companies to secure their assets and they would require non-disclosure agreements to be signed between the parties to protect that information.

Under IA-Pre, that proprietary information is released solely to the government under IA-Pre and not to a potential competitor.

Asset owners allowing resale of their product who have approval under IA-Pre will only be required to submit their asset ratings through the prime, instead of proprietary information.

Due to the varying lengths of contracts and their expiration dates, IA-Pre should be fully installed by 2025, Reece said.

Grason said she doesn’t think commercial SATCOM will ever totally supplant MILSATCOM. “The government should always have assured access and command and control but I do think we’re being savvy in how we incorporate commercial SATCOM through our partnerships with companies and what we’re looking at.”

“One of the things the office is looking at is setting up strategic contracts that don’t just enable customers to buy a service, but also influence and take control over a capability,” Grason said. “For example, a commercial company could send up a satellite constellation, managing those satellites as a network within a network. A government agency could then have access to a subset of those satellites and operate those independent of others.”

“It would give us unprecedented access and control over a system in a way we haven’t had before,” Grason said. “It’s not an uncommon way of doing business on the terrestrial side – think of fiber-optic cables via long-term leases with the carriers. It wouldn’t replace our primary way of doing business, but would offer another really creative model to buy greater access and autonomy than we have today.”

“If commercial industry can build it, bundle it into a capability that can be acquired as a service, it takes away an administrative burden for the government,” Grason said. “We’re trying to structure our contracts to help with that.”

“Under the leadership of Col. Albert Olagbemiro, the new Commercial Services Offices (to include CSCO) will be looking into acquiring commercial services for a variety of other services, from tactical ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) to commercial weather services and situational awareness data,” Grason said. “This is a great thing for the U.S. Space Force because you have an office that is singularly focused on commercial technologies.”

Companies interested in learning more about IA-PRE can contact Reece at disa.meade.ns.mbx.comSATCOM-iapre@mail.mil

Space Systems Command is the U.S. Space Force field command responsible for rapidly identifying, prototyping and fielding resilient space capabilities for joint warfighters. SSC delivers sustainable joint space warfighting capabilities to defend the nation and its allies while disrupting adversaries in the contested space domain. SSC mission areas include launch acquisition and operations; space domain awareness; positioning, navigation and timing; missile warning; satellite communication; and cross-mission ground, command and control and data.

Contact Space Systems Command at SSC@spaceforce.mil follow on LinkedIn.

U.S. Leads in Satellites, But Other Nations Working to Catch Up

The United States has the largest number of satellites on orbit of any other country in the world, but other nations – including China and Russia – are working to catch up.

Stephen C. Pluntze

“For a time, only the most resource-centric countries – the U.S. and the then-Soviet Union – had the wherewithal to build these types of assets,” said Stephen Pluntze, executive director of Space System Command’s (SSC) International Affairs Office.

“Driven by Cold War realities, we had to develop rockets, develop satellites and figure out how to run the ground systems.” Pluntze said. “Then create master command-and-control and analyze the data – none of which had been done before, by anyone. Space is such a broad force multiplier: it enhances all the capabilities you have on the ground, on sea and in the air and makes them stronger.”

But now other countries are working to catch up to the United States in terms of space capabilities and numbers of satellites, said Kevin Mattern, technical director for the Intelligence Directorate at SSC.

“There are three main reasons why: there are economic opportunities in space; there is the national pride of being a space- faring nation and in having the technology to become an independent space-faring nation; and also strategic reasons – space enables many other military operations,” Mattern explained.

“The first thing to remember is, it’s OK and it’s understandable for the other nations of the world to catch up to the United States,” Pluntze said. “As they make progress and we can make them our partners, we then become a much more powerful unit.”

“The countries that we partner with in space are not going into it blindly – they understand the idea of a space coalition: a group of like-minded nations that a group of like-minded nations that creates capabilities that work together,” Pluntze said. “And when we partner we want to work together from the beginning,’ – we call that ‘Allied by Design’ in the International Office.”

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, as of September 2021, there were a total of 4,550 operating satellites in space. More than 3,000 defunct satellites also continue to orbit the planet. Of the active ones, the United States had the most active satellites – nearly 2,800– followed by China with more than 430, Russia with close to 175 and the rest of the world with more than 1,100.

Most of these satellites — 3,790 — operate in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). There are an estimated 139 satellites in Medium Earth Orbit (MEO), 56 in elliptical orbits and 565 in Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO).

Roberta Ewart

“Since 2018, the mega constellations driven by commercial interests have added large numbers of spacecraft,” said Roberta Ewart, SSC Chief Scientist. “If mega constellations actually populate to their envisioned numbers, this could be upwards of 60,000 low Earth orbit entities.”

“These increasing numbers will naturally lead to a discussion about the ability to track, conduct collision avoidance and, on a larger scale, coordinate numerous systems devised by different entities,” Ewart said. “I believe we have the technology to do these tasks, but lag in the policy to create norms of behavior.”

Most of the operational U.S. satellites are commercial satellites. A 2018 report from the National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) broke down the composition of space assets down even further, finding that most of the active satellites were communications satellites from 45 different countries, with the United States accounting for nearly half of these, followed by China, Russia and the rest of the world.

Thirty-eight countries fielded the next-largest category, satellites dedicated to intelligence, surveillance and remote sensing. The United States had more than half of these, followed by China, Russia and the rest of the world.

Only six countries fielded navigation satellites and while the United States had the most, Russia and China were not far behind Pluntze said it’s not hard to see why certain types of satellites dominate in numbers. It all comes down to which missions are a priority to a nation. Communications satellites, which allow people to speak to anyone, anywhere on the planet, almost instantaneously, are tremendously important, particularly from an economic standpoint.

Intelligence-gathering outweighs navigation if GPS is readily available for free. However, Mattern noted, “The world has been relying on GPS, but China, Russia and the European Union have developed their own to be less reliant on the U.S. system.”

Nearly a third of the scientific, technology development or other satellites belong to the United States, followed by China and Russia, according to the NASIC. A total of 38 countries fielded satellites in this category. Pluntze said there’s a distinction between being a space-faring nation and a space-capable one. While the European Space Agency has 22 member nations, only the United States, China and Russia have sent humans into space.

“Smaller nations that are space-faring but not space-capable are going to be relying on partnerships,” Mattern said. “But there are more launch opportunities, both at a governmental and commercial level now than there’s ever been, and competition in the commercial sector drives innovation and drives down costs.”

“Advances in technology have reduced the cost of space capabilities to the point that more nations can be space-faring vs space-capable: they can pay someone to build a satellite and launch it,” Pluntze said. “There are probably no universally recognized definitions of either term, and in reality it’s a sliding scale.”

“Having the expertise in your own country to manufacture satellites and launch vehicles and the national desire to do so, that would be the space-capable end of the scale,” Pluntze said. “Many countries are on their way from one end to the other. But more countries are joining both of those clubs. You’re also seeing a democratization of space with the proliferation of launch opportunities, both rideshare and dedicated, as well as the emergence of on-orbit servicing and smallsats providing military utility.”

“You’ve heard USSF leaders say ‘Space is hard’ and it is – it’s a very unforgiving environment and if you do launch a satellite and it breaks, you can’t get it back,” Pluntze said. “You have to be very deliberate about the planning, creation and operation of your space resources. But any successful technological development is a source of pride and with technology increasing and the expense coming down, more countries are going to be willing to take a chance on it.”

“I think what we’re seeing is a wide breadth of space capabilities being developed and operationalized, in all sectors from commercial to military needs,” Mattern added. “The space environment is proliferating at a great pace as more space-faring nations are becoming more and more capable in terms of launch and space services.”

“The definitions matter,” Ewart said, because they can affect policy. What once was ‘independent’ often implied having capabilities in four segments of a space system of systems: ground segment, user segment, launch segment and space segment. It is possible the definition is evolving to now be interpreted as capability in a few or possibly one of those four segments.”

“This evolution of the definition will have effects on our policy efforts, including interactions at the United Nations,” Ewart continued. “Any stakeholder wants to influence the environment in which they operate, but for space, this environment is changing more quickly than we as a world are used to devising norms.”

Work is currently underway by the United States and its allies on establishing international standards of behavior in space, but in all likelihood a final version won’t be completed for at least several years, Ewart said.

“How ‘sloppy’ can someone be in space and still be allowed to operate?” Ewart said. “Who gets to make that decision?

“Our capabilities are pretty good, we continue to improve them all the time, and we bring partners into the mix, so our capabilities – especially as a partnership community – are still very formidable and as long as we keep practicing together and improving together, our space capabilities will stay cutting-edge,” Pluntze said.

Want to learn more about space assets on orbit? Check out these resources...

European Space Agency’s Annual Space Environmental Report

The Union of Concerned Scientists’ Satellite Database

National Air and Space Intelligence Center— Competing in Space