In the early days of space, only governments or large government contractors built satellites and rockets. Today, the space enterprise encompasses many players, including not only governments and large corporations, but also small businesses, universities, and even high schools. The proliferation of small satellites (smallsats) has a large number of new players in the space business as well as new paradigms for access to, and the use of, space.

Policy has not always kept pace. The Outer Space Treaty,1, 2 which forms the basis of international space law, was ratified by the United Nations in 1967. In the intervening 50 years, a patchwork of governance has grown up around the evolving space industry, but most of this policy-making has been reactionary, rather than anticipatory.

This is not unexpected — technology advances rapidly, while good policy takes time to craft. But the result is a policy picture for today’s space enterprise that is complex and confusing, particularly to non-traditional entrants and missions that occupy policy “gray areas.”

A recent white paper produced by The Aerospace Corporation, “Navigating the Policy Compliance Roadmap for Small Satellites,” discusses the applicability of existing policy, and outlines a process for missions to follow to ensure compliance. Today, navigating the approval process for launch, from compliance with high-level treaties to United States (U.S.) law to agency regulations, can sometimes take longer, and prove more complex, than building the satellite itself.

International Treaties and U.S. National Policy

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 stipulates that states “shall be responsible for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental agencies” and requires “authorization and continuing supervision” of space operations. Per the Outer Space Treaty, a nation “on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object.”

This implies that the U.S. government has responsibility over U.S.-owned objects in space, regardless of whether that object is launched by the U.S. or by a foreign launch provider. Similarly, it requires the government to regulate not only government missions, but commercial and private missions as well.

Within the U.S., National Space Policy3 directs safe and responsible operations in space, including protection of the space environment and the electromagnetic spectrum. The National Space Transportation Policy4 outlines the authorities for military, civil, and commercial launch oversight. Commercial space transportation oversight is under the Secretary of Transportation; thus, commercial launches are licensed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

The Responsibilities of the Launch Provider vs. Satellite Owner

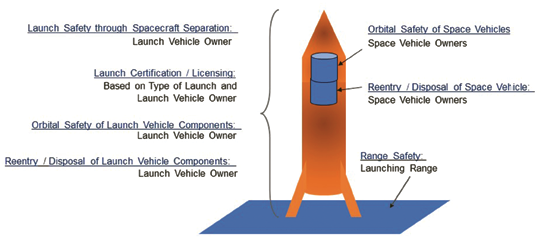

The National Space Transportation Policy, true to its name, discusses mainly access to space in the form of launches, rather than operations in space once satellites have separated from the launch vehicle.

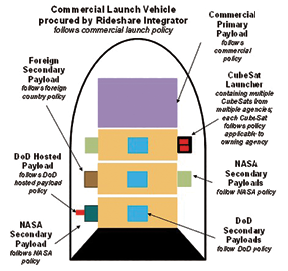

In other words, the launching agency, while responsible for “due diligence” over the satellites it carries, does not maintain authority or direction over those satellites once they are on orbit. Ownership reverts to the “owning agency” once a satellite separates. Figure 1 illustrates the general responsibilities of mission partners on a launch mission and Figure 2 illustrates in more detail how these policy responsibilities break down for a sample multi-payload mission.

It is important at the beginning of a mission to clarify this demarcation and the proper policy compliance responsibilities for all satellites involved. Figuring out who owns each satellite is the first step in this process. However, what constitutes ownership?

The key consideration is, “who will have control authority over the satellite once it launches?” Or, more directly, one can ask, “who has the authority to decide when to execute the satellite’s end of life or deorbit procedure?” So, for example, if the Department of Defense (DoD) makes all critical decisions for a satellite after launch, then it is a DoD satellite, regardless of whether it is built, or operated, by a private company.

Figure 1.

Similarly, if the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) maintains control of all critical decisions, then it is a NASA satellite, even if it is launched on a DoD-owned rocket. Universities who maintain control over their satellites after launch follow commercial regulations for licensing, even if they receive government grants.

Once the owning organization is identified, the appropriate policies can also be identified. The DoD, NASA, the FAA, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) all have broad policy directives that flow down from the National Space Policy; these are discussed in more detail in the white paper. An overview of orbital debris policy, spectrum usage, and imaging approvals is presented here.

Orbital Debris Policy

With the prospect that multiple large constellations of smaller satellites will launch in just the next few years, concerns are rising that orbital debris policy needs modernization and better global compliance. The U.S. has published Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices (ODMSP)5,6,7, which call for such debris mitigation measures as timely satellite disposal after the end of a satellite’s mission, and limitations on the probability of in-space collision or accidental explosion. NASA and the DoD have their own policy documents enforcing these guidelines. Space debris generated by commercial rockets during launch and reentry are regulated through the FAA’s launch licensing processes.

But who polices debris mitigation for private and commercial satellites after separation from the launch vehicle? The surprising answer is the FCC, through its licensing of uplink and downlink frequencies. Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations8 requires applicants for frequency licenses to provide information on their orbits and their plans for orbital debris mitigation.

Regardless of the regulatory agency and approval process, exceptions to ODMSP guidelines require approval at very high levels. Such waivers are increasingly difficult and time-consuming to get as concerns about orbital debris increase.

Figure 2.

Spectrum Usage

Nearly every satellite in space needs to transmit and receive data to and from the ground using radio waves. Public law governs the use of the electromagnetic spectrum to ensure that satellites don’t interfere with each other, or with ground communications. But different agencies regulate different parts of the satellite industry.

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) regulates frequency usage for federal agencies such as NASA and the DoD. The NTIA documents their rules and procedures in the Manual of Regulations and Procedures for Federal Radio Frequency Management.9

Through Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the FCC licenses frequency use for private and commercial satellites — any satellite not owned by the government will go through the FCC for its frequency license. Both the FCC and the NTIA coordinate spectrum usage with the International Telecommunications Union.

Many small, non-traditional satellite operators use amateur frequencies for satellite communications and no frequency license is required. An amateur radio operator simply coordinates with the FCC and submits a pre-launch notification. However, the FCC is applying increasingly stringent tests to ensure amateur frequencies are preserved strictly for amateur use, and not for operational or experimental use. Satellite owners cannot assume that approval will be automatic, and are encouraged to coordinate with the FCC early.

Imaging Approvals

The National Commercial and Space Programs Act10 governs imaging approval for satellites owned and operated by commercial entities and civilian academic institutions. This law assigns authority to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for licensing of imagers. For satellites owned by commercial and civilian academic institutions, NOAA will ensure all imagers also comply with DoD and Intelligence Community requirements for non-Earth Imaging. Government agencies currently have no requirement to obtain licensing for Earth imaging, although it is highly recommended that such agencies seek internal guidance. Non-Earth imaging for operational DoD systems is managed by the Defense Remote Sensing Working Group (DRSWG), but experimental DoD systems fall into a murky policy area, where only interim guidance has been received.

Figure 3.

Earth Imaging

Government agencies currently have no requirement to obtain licensing for Earth imaging, although it is highly recommended that such agencies seek internal guidance. Non-Earth imaging for operational DoD systems is managed by the Defense Remote Sensing Working Group (DRSWG), but experimental DoD systems fall into a murky policy area, where only interim guidance has been received.

Additional Approvals

There are other regulations that govern other aspects of satellite launch and operation, but contrary to popular belief, there is little regulation — other than debris mitigation guidelines — that govern where a satellite can go in space, and when it can maneuver.

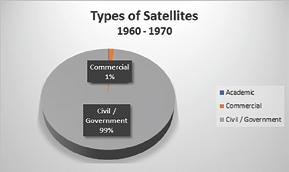

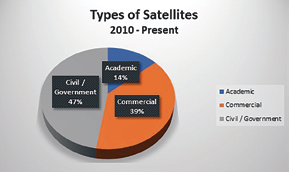

The policy roadmap for getting to space in the first place is still a source of confusion for new entrants, smallsats and other satellites that don’t fit the traditional mold. According to The Aerospace Corporation’s Satellite Database, 1,794 satellites have launched since 2010. Of those, 53 percent were from academic or commercial entities. Compare this to the decade between 1960 and 1970, where 99 percent of the 1,063 satellites launched were government satellites. (Please see Figures 3, below, and 4, next page.) Market research projects that this trend will continue.11 Clearly the space business has changed.

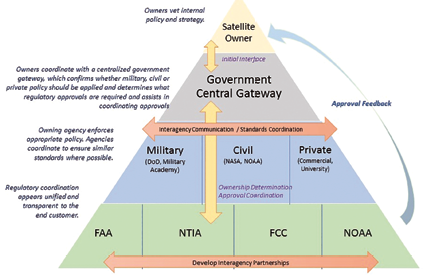

With this change has come increased demand for a less opaque, more streamlined process. Universities and new entrants need guidance; commercial entities seek efficiency. Figure 5 is a simple representation of a “one-stop-shop” approach which could help the current process evolve to meet these needs.

In this approach, a centralized government gateway helps satellite mission owners determine into which policy and oversight “bucket” they fall (government, civil, or private), and then facilitates policy approvals by routing paperwork to the correct regulatory agencies. At the same time, government agencies work together to ensure consistent standards where possible. This approach avoids loopholes, ensures “gray area” missions are properly dispositioned, and provides a clearer policy roadmap to space, for everyone.

www.aerospace.org/

References

1Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, October 10, 1967, United Nations, New York, NY

Figure 4.

2“The Outer Space Treaty: Assessing Its Relevance at the 50-Year Mark”, July 2017, James A. Vedda, The Aerospace Corporation, http://www.aerospace.org/publications/white-papers/the-outer-space-treaty-assessing-its-relevance-at-the-50-year-mark/

3“National Space Policy of the United States of America”, June 28, 2010, White House, Washington, DC

4“National Space Transportation Policy”, November 21, 2013, White House, Washington, DC

5“NASA Procedural Requirements for Limiting Orbital Debris (NPR 8715.6A)”, May 14, 2009, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC

6“NASA Process for Limiting Orbital Debris (NASA STD 8719.14A)”, May 25, 2012, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC

7“Compendium of Space Debris Mitigation Standards Adopted by States and International Organizations”, March 25, 2014, Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, Vienna, Austria

8“Code of Federal Regulations Title 47: Telecommunications”, April 19, 2016, Federal Communications Commission, Washington, DC

Figure 5: Proposed Government Policy Gateway

9“Manual of Regulations and Procedures for Federal Radio Frequency Management”, May 2014, National Telecommunications and Information Administration, Washington, DC

10“United States Code Title 51: National Commercial and Space Programs”, December 18, 2010, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

11SpaceWorks Enterprises, Inc. “2017 Nano/Microsatellite Market Forecast,” http://www.spaceworkscommercial.com, accessed on January 31, 2018.

Eleni M. Sims is a Project Engineer in The Aerospace Corporation’s Space Innovation Directorate. She provides technical support to the Air Force’s Advanced Systems and Development Directorate, specifically the Department of Defense Space Test Program (STP) by architecting cutting edge science and technology missions. She also serves as the corporate knowledge steward for the program. Additionally, she is the lead technical support for three satellites on the STP-2 mission, which is scheduled to launch in early 2018.

Barbara M. Braun received a B.S. in Aeronautics and Astronautics from MIT in 1995, and an M.S. from the University of New Mexico in 2002. She served in the Air Force for a total of 21 years, both on active duty and in the reserves, working on space safety policy for the Air Force Safety Center. She joined the Aerospace Corporation in 2000 and has supported multiple small satellite and rideshare missions for the Department of Defense Space Test Program, the Operationally Responsive Space Office, and NASA.