Only eight years ago, iPhone3 and Android devices debuted with Global Positioning System capabilities and leveraged the U.S. investment in location-based satellite technology for the benefit of commercial industry and consumers.

And the entire GPS industry was born... iPhone3 and Android devices equipped with GPS chips enabled all users to know where they were at any given time, and how to navigate to exactly wherever they needed to go.

Today, GPS-enabled smartphones are being used to perform surveys, maintain electric utilities, to inspect oil and gas pipelines, to direct shoppers around a mall and let the stores deliver ads to them, to dispatch emergency services, to... the list goes on and on and more uses are being added to smartphones every day.

Every worker is now a sensor, just as every soldier is a sensor.

Changing A Job Description

The “every worker is now a sensor” is a spinoff from “every soldier a sensor,” a mantra developed just after the millennium. Then, the adage was primarily a mindset because, while training focused on a soldier’s awareness of change that could turn into intelligence, technology had yet to be developed that could channel that awareness into an actionable endeavor, and all in a timely manner.

Since the advent of the smartphone, more than two billion have been sold worldwide—that number is forecast to grow to six billion by the end of the decade. A large number of smartphones are going to a military that is turning on to the idea that “every soldier a sensor.” This mantra is becoming rather prophetic, thanks to the linkage of mobile devices that are able to send geospatial data to command and, in return, receiving a fused-data picture of situational awareness in near real-time from signals intelligence, Unmanned Aerial System (UAVs), satellite images and full-motion video (FMV), all on a platform that includes history to provide even further context.

This amalgamation of capabilities is saving lives. Every soldier is now a sensor, with the help of ruggedized derivatives of the devices children use to call home when they’re going to be late, and their parents use to make dinner reservations.

The military is coming late to an understanding in a fast developing industry: iPhone and Android devices, along with tablet computers, offer economies and efficiencies of scale in making data gathering data wider spread. They are turning field workers into roaming sensors, capable of exchanging geo-referenced notes, images and video with a headquarters organization and, in return, acting upon decisions that the data drives. Those economies come in using devices that are holding their low price because competition in the industry demands they do so—efficiencies get more pronounced with every iteration of the smartphone.

GPS antennae get better. Russia’s 24-satellite GLONASS system has been added to improve the availability and accuracy on smartphones. Europe’s Galileo will be fully onboard by 2019. China’s BeiDou and India’s Regional Navigation Satellite System sit on the horizon. With each addition to the overall GPS infusions, location-based capabilities will continue to grow, as will the phones’ value as a GPS data collectors for users across the globe.

While phones typically are capable of 3 to 5 meter accuracy, they can achieve higher precision, even centimeter accuracy, when linked with a Bluetooth GPS receiver, such as SXBlue and EOS, to name but two. Accuracy in the centimeter range is getting closer and organizations are facing decisions about their needs, decision that can involve millions of dollars: What data is required to make the decisions that must be made, and what accuracy is required to get that data in quality sets that EW meaningful?

Answering The Phone

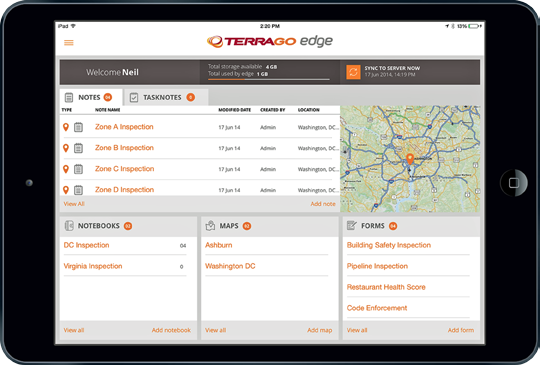

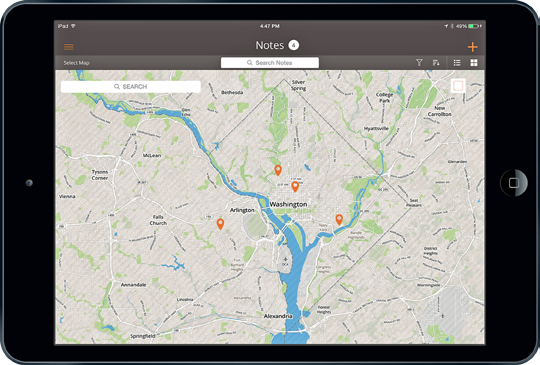

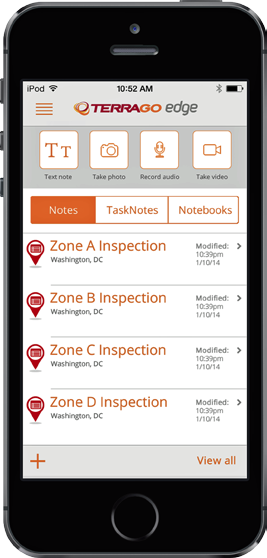

Companies, such as TerraGo, have seized the initiative from old-line, dedicated GPS firms to create software and applications that take advantage of the growing smartphone and tablet computing capability as a data-collection and decision-dissemination device.

For example, TerraGo’s Edge was developed to reduce data collection and field operation costs by syncing what happens in real time. Administrators and field workers experience updates while they work, in a similar manner as the military’s intelligence Grail provides real-time situational awareness.

At one time, companies had to buy expensive, dedicated GPS devices to mine data, smartphones and tablet computers are generating cost savings—so much so that smaller companies are joining their bigger brethren in finding ways to use more data in their operations and decision making. They learn that, where once they saw only expense, a closer examination reveals value and return on investment from more and better location intelligence.

More enabling technology is shortening the time to “every worker a sensor” as geospatial companies use web-based mapping and location services to enable smartphones and tablet computers to become extensions of the home office. That has brought the two entities closer together, operationally.

Where once data went one way, headquarters is now sending information back to mobile devices, bringing field workers into the decision-making process. Team- and consensus-building improves, fostering a climate of information transparency that lends itself to faster, more collaborative decision making. The remote aspect of the field operation becomes less remote. And companies and customers benefit as costs drop, often without exactly knowing why a field force has become more efficient.

Efficiency arrives from the nature of the devices that make the worker a sensor. The devices are bringing industry a workforce that requires less training, as 58 percent of American adults already own smartphones, 42 percent own tablets and both sets have an average of 41 applications on their devices. Seventy-five percent of those apps are location-based.

Managers sometimes have to catch up with the knowledge their new workers possess regarding the ins and outs of mining data—these new workers have been mining data since they were children. A generation raised with the PC is learning from a generation that is using the smartphone to replace the PC. Smartphone sales will be six times that of PCs by 2018, according to an International Data Corp. (IDC) report.

Where once data and intelligence was available only to “the cool kids,” one executive quipped, formerly hierarchically driven organizations find greater success in getting more workers involved at both ends of the data-decision making continuum. That’s because both ends are at the same place and on the same page.

The worker becomes more involved, which equates to a greater possibility of job satisfaction. Organizations that support “Bring Your Own Device” (BYOD) found workers five percent more efficient—those with “Create Your Own Device” (CYOD) logged in at nine percent, according to research done by the Aberdeen Group.

What’s Ahead

An industry that began the democratization of GPS satellite data is already starting to look toward future benefits from space, even beyond Navstar-GPS, GLONASS and other constellations. Google’s recent $500 million purchase of SkyBox is a sign that predictions of a 14 percent increase in the commercial Earth imagery market over the next five years may well be at the low end—the market is already resident at $2 billion.

Technology is evolving and more faithful maps are being rendered from UAVs, satellite imagery and video. The military continues to contribute, with nanosatellites launched by U.S. Special Operations Command being tried as communications relays for a number of far-flung operations.

Other nanosatellite firms are springing up to offer commercial imagery with increasingly vivid resolution. This competition will keep prices low, though some thought must be given to competition that can also inhibit investment.

Nanosats and other satellites already create a data and image deluge that is taxing technology, a problem the military has wrestled with for more than a decade. Small satellites, built more quickly and inexpensively, also present crowd sourcing possibilities that can make data more available and of better quality—however, they must be launched more efficiently and economically in order for the metrics to become more realistic.

More efficient mobile devices... more and better apps... more resources in space... more trained workers... and all are tapping into public and private cloud networks in order to share information from any location on the planet.

This is a race that started eight years ago—so far, this is a sprint that has every sign of becoming a marathon.

Editor’s note: The photo that opens this article is courtesy of the U.S. Army and Sgt. Edward A. Garibay. Shown is Sgt Justin Brady, who was a team leader in 2nd Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 35th Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Heavy Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division, as he checks battlefield locations on a combat smartphone located on his chest, during a Network Integration Evaluation 12.2 exercise at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The system enables Soldiers in combat situations to track the position of friendly forces, mark important locations and to communicate with others.

Mike Gundling is Vice President of Product Management and Marketing at TerraGo. Gundling is a dynamic, high-tech product executive with more than 20 years’ experience in launching market-changing products in the radar, satellite-based navigation, air traffic management and enterprise mobility software industries . To learn more, please visit www.terragotech.com.